Recent Enforcement Developments and Trends Regarding China's Cybersecurity Law

Since the Cybersecurity Law of China took effect three months ago, various peripheral regulations have been published by the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) and other related agencies. These regulations have facilitated the interpretation and implementation of the Cybersecurity Law on different subjects, such as personal information protection, cross-border data transfer and related guidelines, security assessment for internet-based new businesses and protection of critical information infrastructure. The industry players and observers have been curiously waiting to see how the law is enforced in reality. Recently, the government began strengthening enforcement actions and adopting additional measures, including an entirely online court dedicated to internet-related disputes, in order to show its determination and to give teeth to the Cybersecurity Law. The following is a summary of the new developments and general enforcement trends related to the Cybersecurity Law.

1. Investigations Against Major Internet Companies for Potential Content Violations

On August 11, 2017, CAC made an announcement on its official website indicating that the Beijing and Guangdong branches of CAC, under the guidance of the State-level CAC, have opened investigations into the online information exchange and social networking functions operated by three China internet giants: WeChat (the most popular Chinese social media mobile application operated by Tencent, and initially compared to WhatsApp or Facebook but now with far more active users and more services), Sina Weibo (a microblogging service operated by the NASDAQ-listed company with Sina Corporation and Alibaba Group as its two largest shareholders, and often viewed as the Chinese counterpart of Twitter), and Baidu Tieba (an online communication platform operated by Baidu, the Chinese search engine company often viewed as the counterpart of Google). The CAC announcement pointed to violence and terrorism, defamation and pornography as content prohibited by Chinese laws, and alleged that such illegal content published by users of the three investigated platforms were not properly prevented or removed by the platform operators, thus potentially violating the Cybersecurity Law and its related regulations. Investigations into these three online platforms are still underway without further details having been disclosed, except a vague official announcement that investigation results will be published by its local branches after the case closes.

Articles 47 and 48 of the Cybersecurity Law require “network operators” to monitor the information published by the users of their products/services. The operators are obligated to remove any information that is prohibited by laws and regulations, and to record and report such incidents. The above investigations launched by CAC are apparently aimed at sending a strong message to the industry and the public for the implementation of these two provisions under the Cybersecurity Law.

2. General Trends of Content Violations and Enforcement

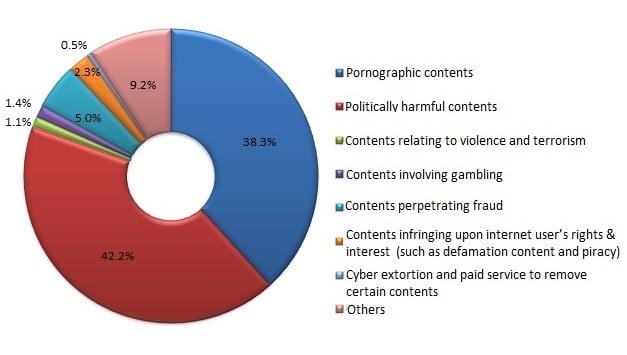

Content monitoring seems to have been a priority on the enforcement agenda. CAC has set up a national hotline and a dedicated website to handle whistleblower complaints regarding illegal content. As disclosed on CAC’s website, within one month after the Cybersecurity Law took effect, about 3.7 million incidents of illegal content were reported, and CAC categorized them into eight segments with distribution as shown in the below chart.

Source: http://www.cac.gov.cn/2017-07/28/c_1121396352.htm

The CAC website also reports that 10 major Chinese internet companies (including Tencent, Sina, Baidu, Alibaba, etc.) in June 2017 had received, handled and transferred to regulators around two million reports of illegal content, with Tecent topping the chart in total number of reports.

Another CAC press release stated that during the second quarter this year CAC had achieved the following in its enforcement actions: (i) conducting preliminary investigations on 443 websites resulting in censures issued to 172 of them, (ii) coordinating with MIIT to have the ICP licenses revoked for 3,918 websites, (iii) ordering websites to revoke over 810,000 user accounts implicated by illegal content or activities, and (iv) transferring 316 cases to police authorities for criminal investigations.

3. Sanctions Against BOSS Zhipin

Based on reports in the public media, another high-profile case involved BOSS Zhipin, a mobile app serving as platform for talent recruitment and job application. Li Wenxing, a recent graduate of a university in northeastern China, used BOSS Zhipin to apply for a job in May 2017 and mysteriously died two months later, shortly after taking the job advertised on this app. Police started an investigation into the death of Li and discovered that the job ad that he responded to on BOSS Zhipin was a fraud, and that the company that had recruited Li was later found to be a criminal organization engaging in an illegal pyramid scheme. CAC’s branches in Beijing (where BOSS Zhipin is based) and Tianjin (where the purported recruiter was located) subsequently opened an investigation into BOSS Zhipin’s activities on August 11, 2017, ordering the operator to take immediate corrective action, to enhance monitoring of content published through the app, to verify the identities of the parties publishing information through the app, and to “clean up” all of the illegal information.

A spokesperson of Beijing CAC cited Articles 24 and 48 of the Cybersecurity Law, saying that BOSS Zhipin violated such provisions for (i) publishing information for its user who hadn’t provided the app with true identification information, and (ii) failing to effectively monitor the information published by such a user. Article 24 of the Cybersecurity Law specifically requires that “network operators” must demand true identification information from users before providing users with internet services, including internet access, domain name registration, instant messaging and online publishing.

4. Targeted Review of Privacy Clauses of 10 Selected Internet Products/Services

CAC and three other Chinese ministries — the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT), the Ministry of Public Security (MPS) and the Standardization Administration of China (SAC) — launched a special operation for enhancing personal information protection in July. As the first project under this special operation, the National Information Security Standardization Technical Committee (also known as TC 260), under the guidance of the above four agencies, will conduct a targeted review of the privacy clauses of 10 selected internet/mobile products/services. This will include WeChat, Sina Weibo, Taobao (the largest Chinese online shopping website, similar to eBay, operated by the NYSE-traded Alibaba Group), JD.com (the second largest B2C online retailer in China), Gaode Map (the top mobile map app in China, delisted from NASDAQ after being acquired by Alibaba Group in 2014), Baidu Maps (a web mapping service operated by the Chinese search engine giant Baidu), Didi (the top taxi hailing app in China that acquired Uber’s China operations in 2016), Umetrip (a mobile flight booking and scheduling information app owned by CAAC) and Ctrip (the largest Chinese online travel booking platform).

As indicated by the official press release on CAC’s website, such targeted reviews would focus on whether the privacy clauses have clearly been conveyed to the users in the following areas: (i) the scope of personal information being collected and how such information is collected; (ii) how the collected personal information will be used, including whether the user will be profiled and the purpose of such profiling, whether it will be used to send targeted commercial ads, etc.; and (iii) the users’ rights to access, removal and correction of their personal information, and how they may exercise such rights as well as any conditions and restrictions thereof. The relevant companies will be required to first conduct a self-review and revise their privacy clauses if necessary, and then the expert working committee led by TC 260 will conduct a further review. The review process is expected to conclude in late September of 2017.

Articles 40-44 of the Cybersecurity Law stipulated the obligations of “network operators” in relation to collection, use, disclosure and handling of personal information. Basic rules include that personal information must be collected and used in a “lawful and proper” manner, limited to the extent necessary; rules shall be disclosed regarding collection and use of the information; consent shall be sought from the data subject regarding the collection and use; personal information shall not be disclosed to third parties without consent of the data subject unless such information has been de-identified; data subject has the right to demand operators to remove or correct their information; and operators need to take appropriate security measures to prevent data breaches and shall report to the government when a breach occurs. As in many other jurisdictions, such rules are broad and leave significant latitude for interpretation and application. Therefore, it will be illuminating to watch developments of this first case of official review of privacy clauses led by TC 260 on the 10 companies (all being leaders in their own business areas) to gain some practical guidance on various open issues, such as what is considered “necessary,” what is effective notice and consent, etc.

5. Crackdown on Personal Information Crimes and Judicial Interpretations

Since March 2017, MPS has started a crackdown on criminal offenses involving cyberattack and abuse of personal information, which resulted in about 1,800 criminal cases opened and about 4,800 individuals arrested as of July 18, 2017, based on public media reports. The Supreme People’s Court and the Supreme People’s Procuratorate of China jointly published a judicial interpretation effective June 1, 2017, which clarified the elements to be established for conviction of the crime of “infringement of citizen’s personal information” under Article 253 of PRC Criminal Law. In particular, collection, sale or offering of personal information to third parties in violation of the applicable laws and regulations (including the Cybersecurity Law) may be prosecuted and convicted if certain thresholds are met, including among others that the involved personal information (i) includes individuals’ whereabouts and such information is subsequently used by other person(s) to perpetrate a crime, (ii) is sold or offered to other person(s) with actual or constructive knowledge that the recipient will use such information to perpetrate a crime, (iii) involves more than (a) 50 pieces of personal information regarding the data subjects’ whereabouts, content of correspondence, credit rating or property ownership, or (b) 500 pieces of personal information of a nature that may affect the personal or property security of the data subjects (such as place of residence or accommodation, records of correspondence, health records and transaction records, etc.), or (c) 5,000 pieces of other types of personal information, or (iv) involves illegal gains exceeding RMB 5,000.

6. Investigations of Breaches of Internet Security Obligations

The local branches of MPS (known as the “Public Security Bureau” or PSB) in various locations recently investigated incidents involving violations under the internet security obligations established by the Cybersecurity Law, according to news published in the public media.

Chongqing PSB in late July penalized an IDC operator for failure to retain users’ activity logs, citing violations under Article 21-3 of the Cybersecurity Law which specifically requires such records to be kept for at least six months. No monetary penalty was imposed. Instead, the perpetrator was given a censure and ordered to make corrective actions within 15 days.

The local PSB in Yibin City, Sichuan Province, in late July fined a local teachers training website alleging violations of Articles 21 and 25 of the Cybersecurity Law. Article 21 requires the network to be graded in terms of its strategic importance, and requires networks operators to adopt security measures (including organizational and technical safeguards) of proper levels based on their assigned grades. Article 25 establishes network operators’ obligations for emergency plans and breach notices for potential cyberattacks. The website was alleged to have failed to implement a proper security system based on its security grade, resulting in high risks for cyberattack and also for failure to notify authorities about the attacks. The entity operating the website was fined RMB 10,000 and its principal was fined RMB 5,000.

Similar cases also took place in other provinces including Guangdong, Jiangsu and Shanxi in late July.

7. Specialized Court for Internet-Related Disputes

On August 18, 2017, the first specialized court for internet-related disputes was officially inaugurated in Hangzhou, southern China, according to the Xinhua News Agency. Hangzhou is a city where the largest online shopping platform Alibaba Group is headquartered, and it is a dynamic region for e-commerce. This court will operate as a trial court for litigation that used to be subject to the jurisdiction of Hangzhou district-level courts with subject matters being (i) contractual disputes relating to online shopping, online services or small-amount online financing, (ii) copyright disputes relating to the internet, (iii) infringement of moral rights relating to the internet, (iv) product liability disputes for goods purchased online, (v) disputes over domain names, (vi) disputes arising from administrative actions relating to the internet, and (vii) other civil or administrative litigation relating to the internet as may be assigned by the higher-level court (which will be the Intermediate Court of Hangzhou).

Unlike the traditional courts, this specialized internet court will be operated online. The hearings may be held through video or audio conferences, and the court may have direct access to online transaction records operated by internet retail giants such as Alibaba. Public information indicates such a specialized internet court has already been through a test run period from May 1 to August 15, 2017, and it handled around 1,400 cases with an average hearing lasting approximately 25 minutes. While such an internet court has been welcomed for its efficiency, some critics are still suspicious about whether it provides an adequate judicial forum, and how deposition and cross-examination can be effectively conducted online.

Based on the above information, it is absolutely clear that the Chinese government has determined to strengthen enforcement of its Cybersecurity Law diligently and forcefully. Chinese domestic and foreign companies should take note of this fact and make a special effort to ensure that their compliance programs are in order. In this way, with or without a government investigation, they will be always in a better position. As a Chinese proverb says, “Preparedness averts peril.”