Public-private partnerships (P3s) continue to attract favorable political and media attention, particularly as public entities search for solutions to the infrastructure crisis facing U.S. states and local governments. While P3s are certainly an attractive model for infrastructure projects, the temptation to view P3s as an infrastructure silver bullet is one that government leaders should resist. P3s are complicated from a legal, technical and financial perspective, and they must be implemented with care.

This article discusses key risks and contracting issues for a particular type of P3 transaction: the Design-Build-Finance-Operate-Maintain model. It is meant as an introduction to the model — highlighting both its significant upside and its many due diligence imperatives — and will be followed by articles dealing with specific issues in more detail.

P3 CONTRACTING AND RISK

Getting Started: Contextualizing the Public-Private Relationship and Defining ‘P3’

For more than 100 years (in the United States at least), the public and private sector’s discrete roles in the design, construction, financing, operation and maintenance of public infrastructure were well defined: the public sector owns, operates and maintains public infrastructure; it also finances capital improvements for major renovations or new infrastructure. When it comes to delivering large capital projects, the public sector hires the most highly qualified architects and engineers to design the projects and then separately hires the construction contractor that submits the lowest bid to complete the work.

Recently, trends in public finance, design, construction and asset management have shifted, and in the 1990s, the public sector began experimenting with new forms of private sector involvement in public infrastructure. Some governments passed legislation allowing the government to hire one firm to design and construct a project. Done correctly, this improved schedule and budget performance without sacrificing quality. And in extreme examples, the public would enter into a long-term arrangement for a private company to design, construct, finance, operate and maintain a public asset. This last example is, for purposes of this article, the definition of a public private partnership.

To clarify further, when used in this article, the term P3 is not any of the following: an operation and maintenance contract; the development of private land using public funds or tax incentives; the construction of large quasi-public projects (like stadiums), where financing may come from both public and private sector sources; or privatizing (i.e., selling) a public asset. When we refer to P3, we are talking about the long-term — but still temporary — transfer of a public asset to a private sector company that will finance a large construction project, design and construct the project, operate and maintain the asset for a set period of time, and then hand it back to the public sector.

One More Thing Before We Begin: P3s Are Not ‘Free’

As noted, this article assumes the private sector is financing the design and construction of the P3 project. This means the private sector will raise debt and equity to pay for the project with the expectation that these investors will make a return. This return generally comes in one of two forms. In the first, the public sector grants a right to collect tolls or other user fees once the asset is built. This involves a large upfront payment by the private sector participant at the time the contractor is awarded. In the second, the public sector will make what are called “availability payments” to the private sector partner both after the construction is completed and over the course of the term, so long as the project is “available” to the public under a defined set of criteria. In both cases, while the public sector is not paying the actual cost of design and construction when the project is built, it either foregoes the right to collect tolls or agrees to make payments to the private partner for many years after the project is built. These should be viewed as alternative financial models from traditional debt financing, budget surplus or raising revenue via taxes. They should not be viewed as a panacea, and their unique risks must be addressed.

Introduction to P3 Risks and Contracting

Most P3 transactions in the U.S. have dealt with transportation assets, and the Federal Highway Administration has been deeply involved in researching and supporting these projects for many years. Recently, the FHWA published model contract guides for both toll projects and availability projects.

1These guides do an excellent job of explaining P3 contracts and how they work, and they are the primary source material for this article. Anyone interested in P3s should read them – more than once.

Risk No. 1 – Scope of Work or Services – the ‘Risk Transfer’

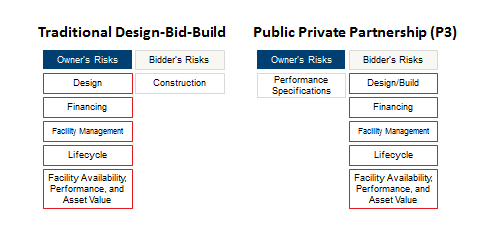

One of the primary advantages P3s offer for the public sector is the transfer of risk to the private sector. The following figure shows the project risk elements that shift from the public to the private sector when using a P3 model:

As you can see, nearly every project risk is transferred to the private sector. Exceptions are captured by certain events that need to be specifically negotiated and scheduled in the P3 agreement. The process of awarding one of these large projects in a fair and transparent way, and within a reasonable time, can be daunting and fraught with peril if not handled properly. In order to effectively transfer risk, the public sector will need to retain experienced technical, financial and legal advisors to conduct the procurement. The high level issues that must be tackled when awarding a P3 contract of this nature include:

- Enabling authority – the state or local government will need a specific statutory (or equivalent) grant of authority to award a P3 contract based on qualifications, financial models and technical proficiency. This is not how traditional public bidding laws – which are based on awarding contracts to the “lowest, responsive, responsible” bidder – work. As such, projects require legislation to authorize the P3 contract and make it legally enforceable. According to the FHWA, 35 states have P3 enabling legislation for transportation projects.2

- Funding – as noted above, P3s are not “free money,” and the public sector will need to make plans to pay the private sector partner (via the right to collect tolls or availability payments) over the term of the P3 agreement.

- Existing property conditions – infrastructure improvements can be new construction or renovation/expansion of existing assets. Either way, things like ownership of real estate, environmental conditions, utility rights and unique property features are always major factors in the planning and execution of a large project. These issues need to be understood before a P3 contract solicitation.

- Marketability – if there is no one in the private sector willing to take on the risk transfer, then there is no P3 project. The largest and most sophisticated projects can typically only be handled by a small number of private firms in the U.S. — or even the world.

‘Supervening Events’

After assessing the primary risks, the parties need to begin allocating specific project risks in the P3 agreement and related documents. At this stage, P3 financial models carry an inherent tension between the private investors’ need for cost certainty and the design-builder’s need for scope security. The government also plays a role here, to the extent its procurement process allows for negotiation of these risks (which it should). In the FHWA parlance, these risks are referred to as Supervening Events.3

A Supervening Event entitles the private partner to some financial or schedule relief. According to the FHWA, “the global P3 market has developed . . . three different categories of these Supervening Events.”4 These are: Compensation Events, Delay Events and Force Majeure Events. A Compensation Event is one that entitles the private partner to both additional compensation and a time extension. A Delay Event is one that entitles the private partner to only a time extension (i.e., the private partner receives no compensation, but suffers no deduction by the public sector from its right to collect tolls or receive availability payments). A Force Majeure Event, while rare, is a subset of a Delay Event that triggers termination rights (in addition to the right to extend the term without deductions from future compensation).

Whether something is a specific type of Supervening Event depends on the project and the negotiation of the P3 agreement. That said, certain patterns have emerged, and following is a list of risks that must be negotiated as Supervening Events:

- Breaches by the government

- Voluntary changes by the government

- Failure by the government to provide right of way for the work

- Permits

- Environmental conditions

- Changes in law

- Hazardous materials

- Strikes

- Fire or natural disaster

- Differing site conditions

- Utility delays

Each of these risks needs to be investigated before and during the procurement. And put simply, if all of the Supervening Event risks are transferred to the private sector without thought, then the construction pricing can be wildly misaligned with the performance risk. On the other hand, if all risks are investigated to the point of 100 percent certainty, then the schedule for the project will be too long — making it unmarketable. The perfectly executed P3 therefore lies in the middle.

Performance Security

Traditional public sector construction projects in the U.S. require contractors to post performance bonds as security for their performance of the construction contract.5 The broad risk transfer inherent in a P3 can prompt questions about whether performance bonds will be required and at in what amounts. Lenders and investors will also typically require other forms of performance security, such as parent company guaranties and letters of credit. FHWA’s contracting guides do not offer prescriptive guidance on these topics, and they point out that federal regulations on performance bonding “do not specify when or how performance bonding must be used or the amount of such bonding when used . . .”6 The same can also be true in state statutes; however, some states have carried performance bonding requirements over to P3 models.7

With this in mind, it is clear that the topic of performance security needs to evaluated as part of the projects legal, financial and technical due diligence. The FHWA Guide contrasts P3s with traditional projects by noting that the equity investors and lenders suffer the “first loss” and “second loss” on a P3, whereas the government suffers the “first loss” on traditional projects. This is noted as apparent support for the idea that perhaps performance security is not necessary on P3 projects.8 But investors and lenders likely do not share this sentiment, and therefore, some form of performance security is a practical necessity even if the government does not mandate it by statute or in the primary P3 agreement.

Payment for Design & Construction

In a P3 transaction, the private partner’s right to begin collecting payments (through tolls or availability payments) will not arise until construction is complete (with the exception of milestone payments, which are not discussed in this article). This means the private partner’s financial model must work from a cash flow perspective. The financing will likely mandate a firm fixed price for the design-build contract (rather than a pure unit price contract). And, in all likelihood, the lender’s technical advisor will have the ability to approve monthly construction draws. If the contracts are not clear with respect to pricing, measuring work in place and contingencies, then the project can be fraught with problems caused by misaligned work and payment. Another issue is payment security. As the state statute summary on payment and performance bonds makes clear, P3 projects are hybrids when it comes to traditional payment security. They involve the improvement of public assets through the use of private financing, yet traditionally, payment on public projects is secured through payment bonds, whereas payment on private projects is secured through mechanic’s lien statutes. How does one record a lien on debt and equity raised to pay for construction when the equity investors have no fee ownership interest in the real estate? It is possible a lien could be recorded against the concession interest, but the better answer is that the P3 enabling legislation should clarify how — and if —subcontractors and material suppliers can protect their payment rights.

This issue was recently addressed on the I-69 Section 5 project in Indiana, where the lead design engineer filed a lawsuit against the payment bond surety and the surety rejected the claim in part based on the fact that the statute did not mandate payment bonds. See Aztec Engineering Group, Inc. v. Liberty Mutual Insurance Company, 2017 WL 1382649. Specifically, the sureties argued that the payment bond only covered “labor” and not professional services, and as part of this argument, they focused on the fact that the P3 enabling legislation did to specifically require payment bonds to be posted for the design and construction work. Thus, the parties were left arguing over the express terms of the payment bond and not the statutory requirements for protecting subcontractors. Aztec prevailed on summary judgment, but this litigation could have been simplified or eliminated if the statutes were more clear and the contracts were able to track the statutes.

Insurance

Every substantial P3 project requires a custom insurance program. Insurance consultants with P3 experience should be retained early, and the procurement must include a process whereby the public sector consultants can confer with the consultants retained by the private sector teams pursuing the project.

With respect to specific forms of coverage, the Availability Payment Contract Guide offers the following insights:

[t]he insurance policies that the Department will require the Developer to obtain and maintain during the construction and operating phases of the Project are typically listed in an exhibit to the Concession Agreement. During the construction phase of the Project, the required coverage will often include builder’s risk, commercial general liability, pollution liability, professional liability, worker’s compensation, automobile liability, excess/umbrella liability, railroad protective liability and marine or aviation liability if appropriate. During the operating phase of the Project, the required coverage will often include “all-risk” property coverage, commercial general liability, pollution liability, professional liability, worker’s compensation, automobile liability, excess/umbrella liability, railroad protective liability and marine or aviation liability if appropriate. Additional types of insurance coverage may be specified depending on the needs of the Project or the environment in which it will be constructed. The insurance requirements will also typically include the minimum amount of the required coverage, requirements to name entities (such as the Department and, in some cases, Lenders) as additional insured parties, and other terms and conditions specific to each type of insurance coverage.9

In addition to their size, the other unique aspect of P3 insurance programs is their duration. This creates risk of premium cost fluctuation over a long-term contract, and therefore, the P3 agreement often contains terms for adjusting compensation in certain situations. The Availability Payment Contracting Guide contains a sample provision dealing with this and offers the following explanation:

[the public sector] could require the [private partner] to take all risk associated with these unexpected increases, but because the likelihood of their occurring is low while the impact is quite significant, this will most likely result in the [private partner] maintaining a contingency, which is paid for by the Availability Payment, for an event that will probably not occur. As a result, [public sector] typically agree[s] to provide additional compensation to the [private partner] if premiums increase by more than a certain percentage above an agreed benchmark, often by reference to a percentage of the premium cost above risk sharing threshold. The risk sharing threshold is typically set at a level which is high enough to capture genuinely unique events and not ordinary shifts in the cost of insurance (the risk of which will remain with the Developer). The benchmarks are typically set with the advice of an insurance consultant prior to the submission of bids for a Project so that bidders are aware of the maximum volatility they will face in these costs, and actual costs are compared to the benchmarks at regular intervals during the O&M Period of a Project (typically every three years).

Defaults and Termination

Termination of a P3 contract is not like terminating a traditional construction contract. There are investors and lenders involved who stand to lose significant returns on their long-term investments. There may also obviously be sureties. Therefore, termination will always involve multiple parties and complicated financial analysis, even if the construction contractor is not performing or in default. Indeed, the public sector will often be obligated to make payments to the private partner even when there is a Developer Default. This is counterintuitive and should be understood prior to commencing a P3 procurement process. In general, the FHWA provides the following high level summary of issues that need to be addressed in the P3 agreement:

- Define the circumstances under which the Concession Agreement may be terminated early.

- Define the circumstances under which either party will be in default under the Concession Agreement.

- Where appropriate, provide the defaulting party with the ability to cure the relevant default.

- Set out the process that the non-defaulting party must follow if it elects to terminate the Concession Agreement.

- Specify precisely what compensation (if any) is payable by the Department to the Developer if the Concession Agreement is terminated early.10

The guide provides detailed explanation of these concepts both in the context of a default by the public partner and a default by the private partner. Its discussion of termination compensation is particularly instructive, and it provides multiple examples of contract provisions dealing with these difficult concepts.11

CONCLUSION

P3s are game-changing transactions that can offer extreme upside to the public sector. They are therefore tools that should be available for consideration by public officials. By the same token, they are not magic or automatically successful. They are complicated and must be implemented thoughtfully. Thus, understanding the planning, risk allocation and contracting for the transactions is critical.

1See Availability Payment Concessions Public-Private Partnerships Model Contract Guide (https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/ipd/pdfs/p3/apguide.pdf) (the "Availability Payment Contracting Guide") and Model Public-Private Partnerships Core Toll Concessions Contract Guide (https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/ipd/pdfs/p3/model_p3_core_toll_concessions.pdf); (the “Toll Concession Contracting Guide); capitalized terms not defined in this article have the meaning set forth in the Availability Payment Contracting Guide.

2 See https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/ipd/p3/legislation/

3 See Availability Payment Contracting Guide, at 69.

4 Id.

5 See, e.g., 4A Bruner & O'Connor Construction Law §§ 12:1 - 12:3.

6 See Availability Payment Contracting Guide, at 17.

7 See http://www.performancebond.com/pdf-forms/p3-state-rules-for-surety-bonding.pdf (summarizing state statutory payment and performance bond requirements for P3 projects and compare Colorado (no requirements) with Indiana (bonds are optional) with Arizona (bonds are mandated but the amounts are at the DOT’s discretion)).

8 Id. at 19.

9 Id. at 60.

10 Id. at 98.

11 Id. at 98-118.

.svg?rev=a492cc1069df46bdab38f8cb66573f1c&hash=2617C9FE8A7B0BD1C43269B5D5ED9AE2)